Page controls

Page content

Since 2010, the TPS and TPSB have implemented various programs, policies, and procedures to address racial profiling, racial discrimination, and anti-Black racism, including the:

- Police and Community Engagement Review (PACER)1

- TPS Equity, Inclusion and Human Rights (EIHR) unit2

- TPSB Anti-Racism Advisory Panel (ARAP)3

- TPSB Race and Ethnocultural Equity Policy (EEP)4

- TPSB Human Rights Policy5

- TPS Human Rights Strategy and Procedure6

- Project Charter between the TPS, TPSB and the OHRC7

- Neighbourhood Officer Program.8

This chapter addresses the need for a distinct TPS procedure and TPSB policy on racial profiling, and summarizes the changes to TPS training during the Inquiry period to address systemic issues. The chapter also identifies critical gaps in training that demonstrate the need for a comprehensive evaluation of all training.

Racial profiling

Evidence of systemic racial profiling can be found in an organization’s formal and informal policies, procedures, and decision-making processes. Discretionary, less-formal processes combined with under-monitored, less-regulated decision-making provide opportunities for ambiguity, subjectivity, and racial bias.

Currently the TPSB and TPS do not have distinct policies or procedures on racial profiling.9 The absence of such policies and procedures has been recognized as a factor that inhibits trust between Black communities and the police, and may contribute to incidents that can contribute to a breach of the Human Rights Code.10

The OHRC found no distinct definition of racial profiling in TPSB policies or TPS procedures, despite the existence of definitions for racial disparity, racial disproportionality, racial equity and inequity, intersectionality and racially biased policing in TPS procedures., Racial profiling is subsumed as a concept under racially biased policing. None of the TPSB policies or TPS procedures identify or prohibit activities that amount to racial profiling. Principles from case law are not articulated, and clear roles and responsibilities for officers, supervisors, the Chief of Police, and TPSB are not defined.

The absence of clear policies and procedures on racial profiling has been recognized as a factor contributing to racial discrimination in the United States.

California

California’s Racial and Identity Policing Board (RIPB) was created by state legislation to eliminate racial profiling and improve racial sensitivity in law enforcement. Its mandate includes publishing an annual report with policy recommendations for eliminating racial profiling. It drew from a range of stakeholders such as law enforcement, academic, governmental and non-profit organizations with relevant expertise to compile best practices.11

The RIPB stated that “Foundational to any bias-free policing policy should be the inclusion of a clear written policy and procedure regarding an agency's commitment to identifying and eliminating racial and identity profiling if and where it exists.”12 The RIPB stated:

Agencies should create a separate policy dedicated to bias-free policing that expressly prohibits racial and identity profiling. The policy should explicitly and strongly express the agency's core values and expectations when it comes to bias-free policing … The policy should clearly articulate when the consideration of race, ethnicity, disability and other protected characteristics is inappropriate in carrying out duties and when it is legitimate policing to consider them (e.g., when a specific suspect description includes race or other protected characteristics).13

Baltimore

The Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has linked the failure to create adequate policy mechanisms in Baltimore to racial disparities and low community trust.

The DOJ found the failure of the Baltimore Police Department (BPD) to have adequate policy mechanisms, among other things, to prevent discrimination, contributed to the large racial disparities in BPD’s enforcement that “undermine the community’s trust in the fairness of the police.”14

For example, the BPD lacked a fair and impartial policing strategy until 2015, “despite longstanding notice of concerns about its policing of the City’s African-American population.” Before enacting its Fair and Impartial Policing policy in 2015, BPD only had a general prohibition against discrimination, which did not provide sufficient guidance to officers on how to conduct their policing activities in a non-discriminatory way, although it did provide a basis for the BPD to discipline officers.15

The TPSB and TPS

Numerous reports, including the TPSB’s own Police Reform Report, have recognized the need for policies and procedures on racial profiling.

Recommendation 45 of the Police Reform Report recommends that the Chair and Executive Director of the TPSB explore and report on the Board’s ability to enact a policy where all instances of alleged racial profiling and bias are investigated and addressed.16

The OHRC has previously recommended that its policy on eliminating racial profiling in law enforcementxvii be adopted by the TPSB and TPS. The TPSB has advised that it will consider this policy as it implements the recommendation from the Police Reform Report and is “open to the idea of considering the need for a stand-alone policy on racial profiling, based on the guidance recently provided by the OHRC.”18

Given the large racial disparities the OHRC documented in the Inquiry’s reports, it is imperative that the TPSB and TPS develop strong and coherent policies and procedures to address and combat racial profiling.

As noted above, evidence of systemic racial profiling can be found in an organization’s formal and informal policies, procedures and decision-making processes. The less formal the process, and the less closely decisions are regulated or monitored, the more opportunity there is for ambiguity, subjective considerations, discretionary decision-making and racial bias to come into play.19

Other Ontario Police forces have begun to enact such policies. For example, the Peel Regional Police (PRP) has updated a directive on Racial Profiling and Bias-Based Policing in response to HRTO decision Nassiah v. Peel (Regional Municipality) Services Board.20 The directive, which includes procedures, training, and accountability, will be used to familiarize all PRP personnel and address profiling and biased policing.

At a minimum, TPSB and TPS policies and procedures must include:

- a definition of racial profiling

- how racial profiling can be identified by TPS officers

- a strict prohibition on racial profiling, and

- accountability mechanisms, including disciplinary consequences for any breach of the policy.21

For the OHRC’s recommendations on a racial profiling policy, see Recommendations 38 and 39.

Training

When the Inquiry began, the OHRC undertook to review TPS training material related to racial profiling and racial discrimination between the periods of January 2010 to January 2017.

The TPS provided various training resources to the OHRC that give snapshots of segments of training programs and outlines for courses.

The OHRC’s review of these resources found several flaws in the TPS training, including:

- insufficient information on racial profiling, racial discrimination, and anti-Black racism

- inadequate explanation of key principles related to racial profiling, racial discrimination, and anti-Black racism, and

- lack of integration of key concepts into broader training programs.

Since our review of these initial documents, the release of the OHRC policy on eliminating racial profiling in law enforcement, the release of the Inquiry’s interim reports A Collective Impact and A Disparate Impact, and subsequent engagements of the OHRC and the TPS and TPSB, the TPS has improved its training.

TPS documents received in 2023 show the TPS has made efforts to ensure their training addresses racial discrimination, racial profiling, and anti-Black racism. For example, the addition of active-bystander training, a dedicated anti-Black racism training developed by subject-matter experts, and scenario-based training on racial discrimination are now part of the In-Service Training. These are steps in the right direction.

2010 to 2017

Each year all TPS officers receive training through the Toronto Police College (TPC) called the In-Service Training Program (ISTP). Officers receive the ISTP training over three days.

Day 1 is dedicated to classroom learning. Days 2 and 3 focus on active training, which includes “dynamic simulations” where officers participate in scenarios involving live actors, firearms, Conducted Energy Weapons (CEW) training, and “judgment training” where officers participate in scenarios through interactive video simulations. The scaffolding approach to training is used, building on the knowledge learned from the ISTP from previous years.22

The OHRC found that the TPS’s 2017 ISTP training resources did not sufficiently focus on racial profiling, racial discrimination, and anti-Black racism. While the training did include some units related to these concepts – such as presentations from Black communities about their lived experiences, a scenario involving a traffic stop of a Black man who felt he was the victim of racial profiling, and a scenario on anti-Muslim bias – anti-racism or discrimination concepts were not fully integrated within the entire course. The lack of integration appeared in several areas of the training. Dynamic simulations, for example, did not include scenarios where officers identify and address racial discrimination.

The training resources also failed to integrate racial profiling, racial discrimination, racial bias, and anti-Black racism concepts into core training sessions. For example, the following training materials provided to the OHRC did not mention these concepts:

- 2014 criminal offences study package for general investigators

- 2016 arrest and release training

- 2017 traffic generalist course

- 2017 provincial statutes course

- 2017 in-service training re use of force.

In addition, many of the documents demonstrated a significant lack of understanding of key principles. Key concepts, such as updated examples from case law and clear roles and responsibilities of officers and supervisors, were missing.

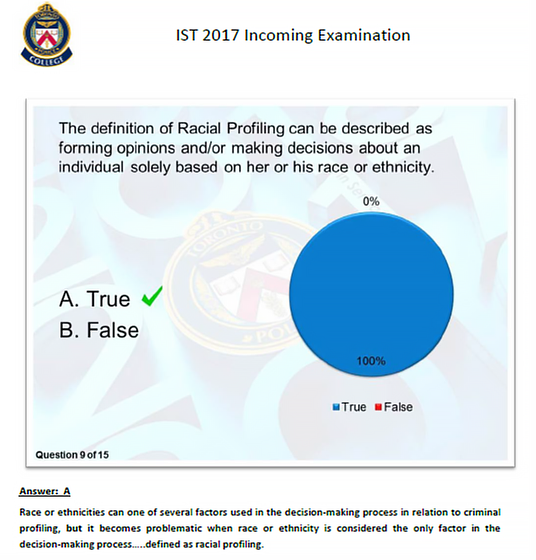

This example shows how the 2017 ISTP misstated a critical legal principle. Instead of recognizing established law that a prohibited ground of discrimination need only be one factor in adverse treatment for there to be discrimination, the training – delivered to all officers – erroneously indicated that racial profiling arises when race is the sole basis for an officer’s decision.23

The error legitimized racial profiling by allowing an officer to use race and ethnicity as part of the rationale for developing an opinion about someone.

Subsequent improvements in training

Our review of documents from 2020 to 2023 demonstrates improvements to TPS training and discussions related to racial profiling, racial discrimination, and anti-Black racism. These changes were influenced by the:

- Loku inquest recommendations

- creation of the TPS’s EIHR24

- TPSB’s Policy on Race-Based Data Collection, Analysis and Public Reporting

- the OHRC policy on eliminating racial profiling in law enforcement, the Inquiry’s reports A Collective Impact and A Disparate Impact, and subsequent engagements of the OHRC, and

- advocacy from racialized communities and the TPSB’s Police Reform Report.

In 2018, the jury in the inquest into the death of Andrew Loku recommended that the TPS develop and implement annual or regular training at division and platoon meetings focusing on the equitable delivery of policing services, stating “The training should acknowledge the social inequities and challenges faced by racialized communities.”25 Topics should include bias-free service delivery and anti-Black racism, and should be provided by reputable, external educators and other experts.26

In 2020, the TPSB’s Police Reform Report directed the TPS to “make permanent the current anti-Black racism training component of the annual re-training (civilians) and In-Service Training Program (uniform).”27

The report also directed the Chief of Police to create a permanent and stand-alone training course that includes:

Anti-racism; anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism; bias and implicit bias avoidance; interactions with racialized communities … an understanding of intersectionality; the importance of lived experience in developing understanding and compassionate service delivery.28

The TPS is also in the process of rolling out several new initiatives in their recruit training. As of December 2022, TPS recruits receive a five-day course called “Fair and Unbiased Policing.” This course includes a review of human rights legislation, Black experiences, anti-oppressive practice, mental health and addictions, ethical inclusion leadership, emotional intelligence, and trauma and self-care and compassion delivery.29

Superintendent Frank Barredo of the TPC explained that the concepts from this course are interwoven throughout other areas of the recruits’ training. For example, in dynamic simulation training, instructors assess recruits on their ability to demonstrate concepts learned in the classroom.30

As part of the Fair and Unbiased Policing course, recruits also receive active-bystander training, which instructs officers to intervene when witnessing misconduct. The training includes overcoming inhibitors to intervention, such as fear of reprisal, fear of embarrassment, and natural deference to seniority and obedience, and focuses on empathy. The training is scenario-based and recruits are evaluated based on instructors’ observations.31

Training for officers through the ISTP has also evolved.

On Day 1 of training, the 2020 ISTP included a first-ever 30-minute module entitled “Anti-Black racism in policing and its effects.”32 Content included:

- the City of Toronto’s Confronting Anti-Black Racism Unit’s definition of anti-Black racism and the OHRC’s definition of racial profiling

- Canadian historical roots of anti-Black racism

- common anti-Black stereotypes

- research supporting “Black threat implicit bias,” and

- examples of racial profiling in suspect selection and through third-party information.33

Senior management within the TPS indicated that anti-Black racism training was integrated throughout the three days of the 2020 ISTP, including in use-of-force training.34 However, based on the OHRC’s review, the second and third days (simulation training) did not appear to integrate concepts of racial profiling, racial discrimination, racial bias, or anti-Black racism in stop, search and questioning activities, charges and arrests, and use of force.35

The 2020 ISTP did include a dynamic scenario where officers are responding to a radio call about a suspicious person. The training manual states that learning points include “the importance of maintaining bias free encounters,” “the value of being able to identify criminal profiling versus bias based profiling” and the requirement that “interactions never violate the Human Rights Code.” However, race or other prohibited grounds of discrimination are not explicitly part of the scenario.36

The EIHR unit also developed training to implement TPSB’s policy on Race-Based Data Collection, Analysis and Public Reporting. This was done in consultation with Dr. Grace-Edward Galabuzi, an Associate Professor in the Department of Politics and Public Administration of Toronto Metropolitan University, who has extensive experience with anti-racism and social justice.37

In February 2020, all senior officers at the rank of inspector and above, and all civilian managers, received a half-day training on anti-Black racism from the City of Toronto’s Confronting Anti-Black Racism Unit.38

In 2021, the TPS enhanced the anti-Black racism training in the ISTP. The course was developed by a subject matter expert and contained instructions on:

- human rights terminology, including the OHRC’s definition of racial profiling, implicit bias and ways to recognize and address it

- rebuilding trust with Black communities

- bias by proxy, and

- the impact of anti-Black racism.

The course included video scenarios and discussion of anti-Black racism.39 Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the training was delivered by an e-learning course.

The 2022 ISTP included training on bias, anti-Black racism, racial profiling, and racial discrimination. It was delivered in person and builds on some of the concepts discussed in the 2021 course. Topics included intersectionalism,40 being trauma-informed, and the concept of privilege.41 The TPS advised the OHRC that officers were evaluated through knowledge checks and classroom discussion by instructors.42 However, they did not provide any grading schemes, and the OHRC did not find any learning goals in the course training similar to dynamic simulations.

In March 2023, select staff of the OHRC participated in a full-day TPS interactive training at the TPC. The event consisted of samples of various training sessions that TPS officers receive in ISTP, including dynamic simulations. Subsequently, the TPC provided the OHRC with additional details of some components of their 2023 in-service training.

Day 1 of the 2023 ISTP includes lectures in:

- police trauma-informed resiliency

- Indigenous experiences

- incident response

- rights to counsel under the Charter

- peer intervention, and

- centering Black experiences.

Days 2 and 3 focus on active training, including dynamic simulations and judgment training as described above.43

The 2023 ISTP takes steps to integrate knowledge of anti-Black racism into other areas of training, but, as discussed below, further work needs to be done. The dynamic simulations the OHRC participated in involved scenarios requiring officers to draw on a number of areas covered on Day 1 of their training, including de-escalation skills, use-of-force options, knowledge of legislation and regulations, mental health, referrals to community organizations, and trauma-informed practice.44

Both dynamic simulations and judgment training video scenarios are followed by a debriefing session, and each scenario includes a list of criteria of anticipated responses and learning points that instructors use to evaluate officers.45 Superintendent Barredo also stated that recruits received the same scenarios as active officers in the 2023 ISTP.46

Within the ISTP, the 2023 anti-Black racism course, Centering Black Experiences, is 80 minutes long (in contrast to the 30 minutes received for the 2020 ISTP). It includes education, history, and some practical guidance for officers interacting with Black persons in a trauma-informed manner.

One of the main themes of this training is racial trauma. It recognizes the longstanding government policies, histories, legacies, and erasure of people of African descent in Canada, and the current psychological and physiological impacts of racial trauma on Black Canadians today. It teaches trauma-informed practice principles, de-escalation methods, and practical tools and strategies to name and reframe harmful stereotypes and support equitable communication.47 It also includes a list of culturally responsive mental health supports for Black communities to which officers can refer people.48

A new and welcome addition to the ISTP is the focus on peer intervention. The goals of the course include building a “healthy culture that expects and accepts intervention, at all ranks, to prevent mistakes, misconduct and to promote wellness.”49 The course discusses circumstances that may require intervention, including misconduct, unethical and discriminatory behaviour, racism, bullying, and microaggressions.

The training discusses intervention techniques that include non-verbal communication, verbal de-escalation, calling for backup and, if necessary, physically restraining a fellow officer.50 Examples of circumstances for intervention explicitly include racism and discrimination.

The above steps demonstrate a positive shift in training following the start of the Inquiry. However, some gaps in training remain that must be addressed.

Gaps in training

Integrating anti-Black racism into other areas of training

More needs to be done to ensure that race, including anti-Black racism, is woven throughout the ISTP. It is not enough to talk about these concepts in the classroom, without ensuring that these discussions continue in every aspect of the simulation training.

In the 2023 ISTP, anti-Black racism was only involved in one scenario – a judgment training video that required officers to draw on what they learned from their anti-Black racism classroom training. The scenario encouraged officers to examine stereotypes and bias both from their own perspectives as well as that of the Black complainant. While other concepts from Day 1 like de-escalation and mental health were integrated throughout the ISTP, anti-Black racism was only found in one simulation shared with the OHRC. In addition, other forms of racial and or Indigenous stereotypes were not found in the documents reviewed.

The OHRC participated in a scenario that mimicked the shooting death of Andrew Loku. Yet, our review of the training documents did not identify any discussion of anti-Black racism in relation to the scenario.

Intersection of race and mental health

The TPS’s training engages elements of mental health and race, but as separate concepts. More can be done to address the unique issues arising at the intersection of race and mental health.

In the Centering Black Experiences course, for example, the materials cover racial stress and trauma, and list culturally responsive resources, but do not cover the topic of mental health disorders at the intersection of race.51

Similarly, TPS’s Crisis and Mental Health Awareness training does not discuss the concept of race, and culturally responsive resources are not included in the list of resources.52

As mentioned above, one of the dynamic simulations includes a scenario that appears to mirror the circumstances around the death of Andrew Loku: a person in crisis, holding a blunt object, in an empty hallway with the officer positioned at one end. However, the materials we reviewed in relation to this scenario – including the learning objectives and teaching points provided to instructors – do not address race. Another scenario mimicked the shooting death of Sammy Yatim, yet race and mental health were not discussed in the materials related to the scenario.

One of the dynamic simulation scenarios did address the intersection of 2SLGBTQ+ and mental health. However, the judgment training video scenario (the only one that involved race) did not involve mental health or any other intersectionality. Given the death of Andrew Loku, and other Black people experiencing mental health disorders who have died during interactions with police, it is critical that TPS training and simulations include a specific and detailed discussion of this intersection.53

Evaluation

Effective evaluation includes assessing an individual officer’s understanding of relevant concepts from training, and whether anti-racism training as a whole has an impact on officer behaviour or community outcomes (e.g., whether initiatives reduce racial disproportionalities and disparities). The TPS should take steps to strengthen evaluation of officers and evaluation of all of its training programs.

Officer evaluation

The ISTP is a series of courses over three days that all officers take each year. The courses vary in content and format. As noted above, officers are required to attend lectures on anti-Black racism and officer well-being, participate in firearms training, and undergo dynamic simulation training.

Each course evaluates its attendees differently, if at all. For example, we were advised by the TPC that in the firearms training, officers are tested on their accuracy by evaluating how many times they hit a target. They must pass a threshold to continue to use their firearm.54

For the classroom components of the ISTP, there is no standardized, objective method of evaluating an officer on each learning objective. Superintendent Barredo stated that officers are evaluated on their classroom knowledge during other areas of training, such as dynamic simulation training where they are asked to physically demonstrate and explain actions that reflect their classroom learning.55

In response to the Loku recommendations, the TPS noted that:

In 2018, the Service implemented an incoming knowledge check on day one of I.S.T.P. … Upon completion of day one, officers were required to complete a 14 question outgoing examination. When officers failed to show competence in certain areas, they were required to receive additional training in the identified area. In addition[,] failure to show competence in the remaining two days … resulted in officers having their use of force options removed/suspended[.]”56

However, the material provided for the 2023 ISTP does not appear to have objective criteria that an officer must complete to pass each component of the ISTP. Instead, there is a list of general learning objectives and teaching points. The evaluation standard states:

The instructor will evaluate the learner and their ability to deal with the situation. The learner should display a high-level confidence and competence when faced with this scenario. The learner is expected to abide by all service policies and procedures as well as meet all legal requirements.

- Instructor observation

- Debrief of scenario

- Discussion and feedback from students

- A thorough debrief was held at the end of each scenario to ensure that learning objectives were retained.

It is imperative that the TPS consider implementing standardized and objective testing throughout ISTP. Officers should be required to pass a rigorous evaluation and demonstrate that lessons have been absorbed and retained.

Evaluation of training in reducing racial disparities

In addition to evaluating officers, training in anti-Black racism, racial profiling, and racial discrimination must be evaluated for its effectiveness to determine whether it has helped to reduce racial disparities. This level of evaluation was also recommended by the jury of the coroner’s inquest into the death of Andrew Loku.57

To provide more public interest remedies and to capitalize on ongoing efforts by the TPS to address human rights concerns, the TPSB and TPS partnered with the OHRC to launch the Human Rights Project Charter (Project Charter) in May 2007. The Project Charter was designed to apply a human rights lens to all aspects of policing.58

In 2014, an independent evaluation of the Project Charter recommended that the Toronto police:

- Ensure that subsequent strategies or initiatives in human rights are based on a strong logical model with evaluation tools built in. Establish baseline data prior to the implementation of new initiatives to allow complete assessments.

- Regularly evaluate all existing diversity related training to ensure human rights elements are pertinent and effective. Include a tracking system to measure levels of participation in all mandatory and elective courses.59

The evaluation report also stated that “evaluation of the impact of training on behaviour is required. Implementing feedback loops and evaluation strategies will ensure continuous revisions and improvement to training.”60

TPS training on anti-Black racism and anti-racial discrimination has not been effectively evaluated. Officers taking part in such training have also not been effectively evaluated.

Before 2017, it appears that there was no external evaluation of the effectiveness of training in racial profiling, racial discrimination, or anti-Black racism, and its impact and outcomes on the community.61

At an October 11, 2022 TPSB meeting, Superintendent Barredo stated that the TPC had requested an external review that would conduct this level of evaluation, but they did not receive any bids. The TPSB passed a motion for the Chief of Police to report back in Q1 2023 on “[t]he efforts undertaken to attempt to retain an expert third party resource to externally evaluate training programs offered by the Toronto Police College.”62

While improvements have been made over the last several years, gaps remain that must be addressed in order to ensure that training on anti-Black racism and racial discrimination results in meaningful change.

For the OHRC’s recommendations on training, see Recommendations 40–49.

Chapter 8 Endnotes

[1] TPSB, “Making Progress Together on Police Reform by the Toronto Police Services Board and the Toronto Police: A Six-Month Update,” online: https://tpsb.ca/mmedia/news-release-archive/listid-2/mailid-221-81-recommendations-six-month-update.

[2] TPS, “Equity Inclusion & Human Rights”, online: https://www.tps.ca/organizational-chart/corporate-support-command/human-resources-command/equity-inclusion-human-rights/.

[3] TPSB, “Anti-Racism Advisory Panel (ARAP)”, online: https://www.tpsb.ca/advisory-panels/24-panels-and-committees/94-arap.

[4] TPSB, Race and Ethnocultural Equity Policy (15 November 2010), online: https://www.tpsb.ca/policies-by-laws/board-policies/176-race-and-ethnocultural-equity-policy.

[5] TPSB, Policy on Human Rights (17 December 2015), online: https://www.tpsb.ca/policies-by-laws/board-policies/165-human-rights.

[6] TPSB, “Minutes of Public Meeting: September 17, 2015” (17 September 2015), at 26–27 online: https://tpsb.ca/jdownloads-categories?task=download.send&id=183&catid=7&m=0.

[7] OHRC, “Backgrounder – Project Charter: Ontario Human Rights Commission / Toronto Police Service / Toronto Police Services Board”, online: https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/backgrounder-project-charter-ontario-human-rights-commission-toronto-police-service-toronto-police.

[8] TPS, “Neighbourhood Community Officer Program”, online: https://www.tps.ca/neighbourhood-community-officer-program/.

[9] OHRC interview of Suelyn Knight, Manager, EIHR unit, TPS (5 March 5, 2020); responses of the Toronto Police Services Board to written questions asked under s. 31(7)(c) of the Human Rights Code, RSO 1990, c H19.

[10] Nassiah v Peel (Regional Municipality) Services Board, 2007 HRTO 14 at paras 208–212.

[11] California Department of Justice, Racial & Identity Policing Advisory Board Annual Report, (2019) at 2, online (pdf): https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/ripa/ripa-board-report-2019.pdf.

[12] California Department of Justice, Racial & Identity Policing Advisory Board Annual Report, (2019) at 28, online (pdf): https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/ripa/ripa-board-report-2019.pdf.

[13] California Department of Justice, Racial & Identity Policing Advisory Board Annual Report, (2019) at 28, online (pdf): https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/ripa/ripa-board-report-2019.pdf.

[14] Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice, “Investigation of the Baltimore City Police Department” (10 August 2016) at 8 and 62, online: www.justice.gov/crt/file/883296/download.

[15] Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice, “Investigation of the Baltimore City Police Department” (10 August 2016) at 8, 47, 62, 68 and 129, online: www.justice.gov/crt/file/883296/download.

[16] TPSB, “Minutes of Virtual Public Meeting: August 18, 2020” (18 August 2020), Police Reform in Toronto: Systemic Racism, Alternative Community Safety and Crisis Response Models and Building New Confidence in Public Safety at 7 and 46 (10 August 2020), online: https://tpsb.ca/jdownloads-categories/send/32-agendas/631-august-18-2020-agenda.

[17] OHRC, Policy on eliminating racial profiling in law enforcement (Toronto: Ontario Human Rights Commission, 2019), online (pdf): https://www3.ohrc.on.ca/sites/default/files/RACIAL%20PROFILING%20Policy%20FINAL%20for%20Remediation.pdf.

[18] Responses of the TPSB to written questions at 30, asked under s. 31(7)(c) of the Human Rights Code, RSO 1990, c H19.

[19] OHRC, Policy on eliminating racial profiling in law enforcement (2019) at 4.1.2., online: Ontario Human Rights Commission www.ohrc.on.ca/en/policy-eliminating-racial-profiling-law-enforcement#_Toc17977371.

[20] Nassiah v. Peel (Regional Municipality) Services Board (2007) HRTO 14

[21] Diversity Institute at Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly Ryerson University), “Evaluation of the Human Rights Project Charter” (February 2014) at 43, online (pdf): https://www.torontomu.ca/content/dam/diversity/reports/HRPC_Report_WEB_2014.pdf.

[22] TPC, “Overview of In-service Training to the Ontario Human Rights Commission” (23 March 2023).

[23] Moore v British Columbia (Education), 2012 SCC 61 at para 33; Stewart v Elk Valley Coal Corp, 2017 SCC 30 at para 69 [Elk Valley]; Shaw v Phipps, 2010 ONSC 3884 at paras 11–15, 76, aff’d Shaw v Phipps, 2012 ONCA 155; Peel Law Association v Pieters, 2013 ONCA 396 at paras 53–62 and 111–25; Québec (Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse) v Bombardier Inc (Bombardier Aerospace Training Center), 2015 SCC 39 at paras 40–54.

[24] The EIHR unit replaced the former Diversity Management unit. The EIHR unit’s current operational priorities include the TPS’s race-based data collection strategy; gender, diversity and trans inclusion project; and “systemic review of recruitment to identify any barriers in being able to recruit from all communities.” The EIHR unit is also supporting the Toronto Police College with diversity, inclusion and human rights training. It will also conduct an enterprise-wide accessibility audit and develop a TPS equity strategy. See OHRC interview of Suelyn Knight, Manager, EIHR Unit (5 March 2020); TPSB, “Minutes of Virtual Public Meeting: October 22, 2020” (22 October 2020), Report from Chief Ramer regarding “Toronto Police Service Board’s Equity, Inclusion and Human Rights Unit – Progress Update on the Unit’s Work” (14 September 2020) at 77, online (pdf): https://www.tpsb.ca/jdownloads-categories/send/32-agendas/637-2020-oct-22-agenda; report from Chief Saunders to the TPSB re Equity, Inclusion and Human Rights Unit Structure (27 March 2019) (Minutes of the Public Meeting of the Toronto Police Services Board, May 30, 2019), see Equity, Inclusion & Human Rights Unit Structure minutes and report, online: https://tpsb.ca/jdownloads-categories/send/54-2019/613-may-30.

[24] Office of the Chief Coroner, Jury Recommendations Inquest into the death of Andrew Loku (30 June 2017) at Recommendation 2.

[26] Office of the Chief Coroner, Jury Recommendations Inquest into the death of Andrew Loku (30 June 2017) at Recommendation 2.

[27] TPSB, “Minutes of Virtual Public Meeting: August 18, 2020” (18 August 2020), Report from Jim Hart, Chair, regarding Police Reform in Toronto: Systemic Racism, Alternative Community Safety and Crisis Response Models and Building New Confidence in Public Safety (10 August 2020), Recommendations 52 and 53 at 47, online (pdf): https://tpsb.ca/jdownloads-categories/send/32-agendas/631-august-18-2020-agenda.

[28] TPSB, “Minutes of Virtual Public Meeting: August 18, 2020” (18 August 2020), Report from Jim Hart, Chair, regarding Police Reform in Toronto: Systemic Racism, Alternative Community Safety and Crisis Response Models and Building New Confidence in Public Safety (10 August 2020), Recommendations 52 and 53 at 47, online (pdf): https://tpsb.ca/jdownloads-categories/send/32-agendas/631-august-18-2020-agenda.

[29] OHRC interview of Staff Sergeant Patrick Coyne and Superintendent Frank Barredo of the Toronto Police College (29 November 2022).

[30] OHRC interview of Staff Sergeant Patrick Coyne and Superintendent Frank Barredo of the Toronto Police College (29 November 2022).

[31] OHRC interview of Staff Sergeant Patrick Coyne and Superintendent Frank Barredo of the Toronto Police College (29 November 2022).

[32] Letter from the TPS to the OHRC arising from the interview of Suelyn Knight, Manager, EIHR Unit (13 June 2020).

[33] TPC, Learning Development and Standards section – 2020 In-Service Training Program Day One Course Training Standards; training slide presentation and instructor’s notes re anti-Black racism and its effects on policing.

[34] In an interview with Suelyn Knight, Manager, EIHR Unit (5 March 2020), she stated: “This year, there’s anti-Black racism [training] throughout the three days, instead of the just one day – to recognize anti-Black racism training on the academic side [with] theory for one day and on use of force for two days; and putting that thinking into action - through scenarios, videos, and conversations on de-escalation.”

[35] De-escalation and dealing with people in crisis appear to be integrated into use of force/simulation training. TPC, In-Service Training Program – Day 2 and Day 3 Course Training Standard (2020); TPS, In-Service Police Training Manual (2020).

[36] TPS, In-Service Police Training Manual (2020).

[37] TPSB, “Minutes of Virtual Public Meeting: October 22, 2020” (22 October 2020), Report from Chief Ramer regarding “Toronto Police Service Board’s Equity, Inclusion and Human Rights Unit – Progress Update on the Unit’s Work” (14 September 2020) at 77, online (pdf): https://www.tpsb.ca/jdownloads-categories/send/32-agendas/637-2020-oct-22-agenda.

[38] OHRC interview of Inspector Stacy Clarke (5 March 2020).

[39] TPS, E-Learning Module: Let’s Talk How Anti-Black Racism Affects Impartial Policing (2021).

[40] Intersectionalism is the terminology used by the TPS in its ISTP training.

[41] TPS, 2022 In-Service Training Program for Anti-Black Racism; The Black Experiences slide deck.

[42] OHRC interview of Staff Sergeant Patrick Coyne and Superintendent Frank Barredo of the Toronto Police College (29 November 2022).

[43] TPC, Overview of In-Service Training to the Ontario Human Rights Commission (23 March 2023).

[44] TPC, Overview of In-Service Training to the Ontario Human Rights Commission (23 March 2023).

[45] TPC, Overview of In-Service Training to the Ontario Human Rights Commission (23 March 2023).

[46] OHRC interview of Staff Sergeant Patrick Coyne and Superintendent Frank Barredo of the Toronto Police College (29 November 2022).

[47] TPC, Overview of In-Service Training to the Ontario Human Rights Commission (23 March 2023).

[xlviii] TPC, Overview of In-Service Training to the Ontario Human Rights Commission (23 March 2023) at 33.

[48] TPC, Overview of In-Service Training to the Ontario Human Rights Commission (23 March 2023) at 15.

[49] TPC, Overview of In-Service Training to the Ontario Human Rights Commission (23 March 2023) at 46.

[50] TPC, Overview of In-Service Training to the Ontario Human Rights Commission (23 March 2023).

[51] TPC, Crisis and Mental Health Awareness training (23 March 2023).

[52] TPC, Overview of In-Service Training to the Ontario Human Rights Commission (23 March 2023) at 17–19.

[54] TPS, Incident Response Training (2023) at 51.

[55] OHRC interview of Staff Sergeant Patrick Coyne and Superintendent Frank Barredo of the TPC (29 November 2022).

[56] TPS, “Police Reform Recommendation Summary – PRR#77 (LOKU)” at 6–7, online (pdf): https://www.torontopolice.on.ca/tpsb-reform-implementation/docs/R77_-_Inquest_into_the_death_of_Andrew_Loku_-_Report_to_TPSB.pdf.

[57] Office of the Chief Coroner, Jury Recommendations Inquest into the death of Andrew Loku (30 June 2017) at Recommendation 2.

[58] Diversity Institute at Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly Ryerson University), “Evaluation of the Human Rights Project Charter” (February 2014) at vii, online (pdf): https://www.torontomu.ca/content/dam/diversity/reports/HRPC_Report_WEB_2014.pdf.

[59] Diversity Institute at Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly Ryerson University), “Evaluation of the Human Rights Project Charter” (February 2014) at 44, online (pdf): https://www.torontomu.ca/content/dam/diversity/reports/HRPC_Report_WEB_2014.pdf.

[60] Diversity Institute at Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly Ryerson University), “Evaluation of the Human Rights Project Charter” (February 2014) at 32–33, online (pdf): https://www.torontomu.ca/content/dam/diversity/reports/HRPC_Report_WEB_2014.pdf.

[61] Letter from the TPS to the OHRC arising from the interview of Christopher Kirkpatrick (3 September 2020). For example, officers were not evaluated on the Fair and Impartial training program and there was no evaluation of the impact of the training on officer behaviour or community outcomes.

[62] TPSB, “Minutes of the Public Meeting: October 11, 2022” (11 October 2022), online (pdf): https://tpsb.ca/jdownloads-categories?task=download.send&id=754&catid=62&m=0.